Digitale Ausgabe

Download

| TEI-XML (Ansicht) | |

| Text (Ansicht) | |

| Text normalisiert (Ansicht) |

Ansicht

| Textgröße | |

| Originalzeilenfall ein/aus | |

| Zeichen original/normiert | |

Abbildungen

Zitierempfehlung

Alexander von Humboldt: „On the Mountain-chains and Volcanoes of Central Asia, with a Map of Chains of Mountains and Volcanoes of Central Asia“, in: ders., Sämtliche Schriften digital, herausgegeben von Oliver Lubrich und Thomas Nehrlich, Universität Bern 2021. URL: <https://humboldt.unibe.ch/text/1830-Ueber_die_Bergketten-10> [abgerufen am 26.04.2024].

URL und Versionierung

|

Permalink: https://humboldt.unibe.ch/text/1830-Ueber_die_Bergketten-10 |

| Die Versionsgeschichte zu diesem Text finden Sie auf github. |

| Titel | On the Mountain-chains and Volcanoes of Central Asia, with a Map of Chains of Mountains and Volcanoes of Central Asia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jahr | 1831 | ||||

| Ort | Edinburgh | ||||

|

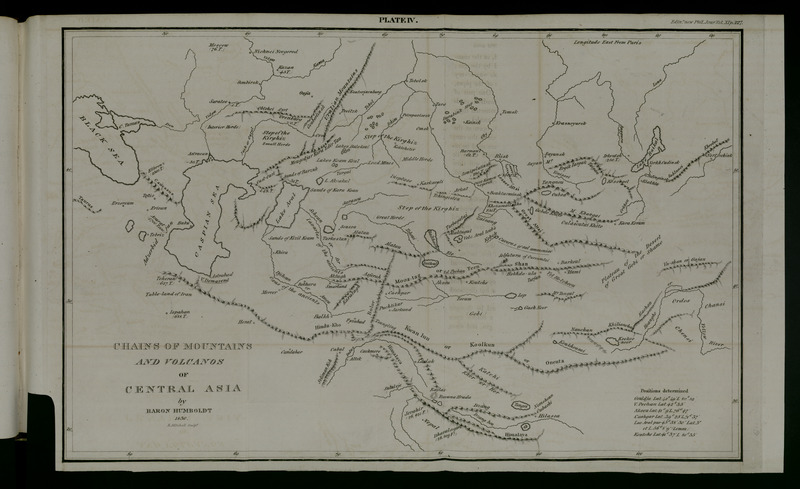

Nachweis in: The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal 11 (Juli–September 1831), S. 227–240; 12 (Oktober–Dezember 1831), S. 145–159, Karte.

|

|||||

| Sprache | Englisch | ||||

| Typografischer Befund | Antiqua; Auszeichnung: Kursivierung, Kapitälchen; Fußnoten mit Asterisken und Kreuzen; Schmuck: Initialen. | ||||

|

Identifikation |

|||||

Statistiken

|

|||||

On the Mountain-chains and Volcanoes of Central Asia, with aMap of Chains of Mountains and Volcanoes of Central Asia.By M. de Humboldt*. (With a Map.)

* This memoir we consider of high importance, as illustrating not onlythe geography, but also the geognosy, of several interesting parts of CentralAsia.|228| Canary Isles *, explained, with much talent, luminous ideasupon the distribution of volcanoes, which are sometimes in isola-ted groups around a central volcano, at other times arrangedlongitudinally in a series. The memoir which I now presenton these volcanic phenomena, situated at a great distance fromthe sea, is certainly much less important; it treats of the localphenomena of Central Asia, and of the interior of South Ame-rica, concerning which I have had opportunities of collectinginformation little known hitherto. We know still so little ofthe kind of mysterious connexion of volcanoes in activity withthe vicinity of the sea, that every thing which relates to a vol-cano of which we learn the existence very unexpectedly in theinterior of a continent, gives a very high interest even to a localphenomenon.The central and interior portion of Asia, which formsneither an immense cluster of mountains nor a continued table-land, is crossed from east to west by four grand systems ofmountains, which have manifestly influenced the movements ofthe population; these are, the Altaï, which is terminated to thewest by the mountains of the Kirghiz; the Tëen-shan, theKwan-lun, and the Himalaya chain. Between the Altaï andthe Tëen-shan, are placed Zungaria and the basin of the Ele;between the Tëen-shan and the Kwan-lun, Little or ratherUpper Bucharia, or Cashgar, Yarkand, Khoten, the greatdesert of Gobi (or Cha-mo), Toorfan, Khamil (Hami), andTangout, that is, the northern Tangout of the Chinese, whichmust not be confounded with Tibet or Se-fan; lastly, betweenthe Kwan-lun and the Himalaya, Eastern and Western Tibet,where H’lassa and Ladak are situated.1. The system of the Altaï encompasses the sources of theIrtish, and of the Yenisseï or Kem; to the east, it takes thename of Tangnu; that of the Sayanian mountains betweenlakes Kossogol and Baikal; farther on, that of the lofty Kentaïand the mountains of Dauria; lastly, to the north-east, it joinsthe Yablonnoy-khrebet, the Khingkhan and the Aldan moun-tains, which stretch along the sea of Okhotsk. The mean lati-

* This splendid and very valuable work we trust to see translated into Eng-lish. If published in octavo, it would be accessible to every geological reader,and find a place in every library of Natural History in Britain.—Edit.|229| tude of its course from east to west is between 50° and 51° 30′.We shall soon have satisfactory notions respecting the geogra-phy of the north-eastern part of this system, between the Baikal,Yakutsk, and Okotsk, for which the world will be indebted toDr Erdmann, who has recently traversed those parts. TheAltaï, properly so called, scarcely occupies seven degrees oflongitude; but we give to the northernmost portion of themountains encompassing the vast mass of high land of InnerAsia, and occupying the space comprised between the 48th and51st parallels, the name of the System of the Altaï, because simplenames are more easily impressed upon the memory, and becausethat of Altaï is best known to Europeans, from the great metal-lic wealth of these mountains, which now annually yield 70,000marks of silver and 1900 marks of gold *. The Altaï, in Turkish,in Mongol, Altaï-in-oola, ‘gold mountain,’ is not a chain ofmountains, forming the limit of a country, like the Himalaya,which bounds the table-land of Tibet, and which consequentlylowers itself abruptly only on the side of India, which is lowerthan the other country. The plains adjoining lake Zaïsang, andespecially the steppes near lake Balkashi, are certainly not morethan 300 toises (1968 English feet) above the level of the sea.I avoid, intentionally, in this paper, conformably to thestatements I collected on the spot, employing the term LesserAltaï, if this term is applied to the vast mass of mountains si-tuated between the course of the Narym, lake Teletsky, theBia, Serpent Mountain, and the Irtish above Oustkamenogorsk,consequently the territory of Russian Siberia, between the 79thand 86th meridians east of Paris, and between the parallels of49° 30′ and 52° 30′. This Little Altaï is probably, owing toits extent and elevation, much more considerable than theGreat Altaï, whose position and existence as a chain of snowymountains are, perhaps, equally problematical. Arrowsmith,and several modern geographers, who have followed the modelhe has arbitrarily adopted, give the name of Great Altaï to animaginary continuation of the Tëen-shan, which is carried tothe eastward of Khamil (Hami) and Barkoul (Chin-se-foo), aManchoo town, and runs to the north-east, towards the eastern

* A mark is equal to 4608 grains.|230| sources of the Yenissëi and Mount Tangnu. The direction ofthe line of separation of the waters, between the affluents of theOrkhon and those of the Aral-noor, lake of the steppe, and theunfortunate practice of marking by high chains of mountainswhere systems of streams separate, have occasioned this error.If it be desired to retain on our maps the name of Great Altaï,it should be given to the succession of lofty mountains rangedin a course directly opposite (parallel to the chain of theKhangai *), or from the north-west to the south-east, betweenthe right bank of the Upper Irtish, and the Yeke-Aral-noor,or Lake of the Great Isle, near Gobdo-Khoto.“There, consequently, to the south of the Narym and of theBukhtorma, which bounds what is called the Little RussianAltaï, was the primitive abode of the Turk tribes; the placewhere Dizabul, their grand khan, towards the close of the sixthcentury, received an ambassador from the Emperor of Con-stantinople. This gold-mountain of the Turks, the Kin-shanof the Chinese, a name with the same signification, bore hereto-fore also those of Ek-tag and Ektel, both of which probablyhave an analogous meaning. It is said that more to the south,under the 46th parallel, and almost in the meridian of Pijanand Toorfan, a lofty peak is still called in Mongol Altaïnniro,‘summit of the Altaï.’ If some degrees farther to the south,this Great Altaï unites itself to the Naiman-ula mountains, wethere find a transverse ridge which, running from the north-west to the south-east, joins the Russian Altaï to the Tëen-shan,northward of Barkoul and Hami †. This is not the place to

* “Mount Khanggay-ula is to the north of the source of the Orkhon. Itssummits are lofty and considerable. This chain is a branching of the Altaï,which comes from the north-west: it extends to the eastward to the riversOrkhon and Tula with their affluents, and becomes the Kenteh of theKhinggan. A branch of this chain separates to the west, and runs to thenorth under the name of the Kuku-daban; it encompasses the Upper Selenggaand all its affluents, which take their origin in it, and then runs a distance of1000 le into the Russian territory. The Orkhon, the Tamir, and their af-fluents, have likewise their sources in this chain, which is probably the samewhich the Chinese distinguish by the name of Yang-jin-shan.—Klaproth.† “The Chinese (in their imperial geography of China), in tracing the direc-tion of the Great Altaï from the north-west to the south-east, make it almostre-unite itself to the Tëen-shan, which corresponds exactly with what M.de Humboldt states.—Klaproth.|231| develope how the system of north-western direction, so generalin our hemisphere, is traced in the beds of the rocks, in the lineof the Alps of Alghin, of the lofty steppe of the Chuya, of thechain of the Jyiktu, which is the culminating point of the Rus-sian Altaï, and in the hollows of the narrow valleys, where flowthe Chulyshman, the Chuya, the Katunia, and the UpperCharysh; lastly, in the whole course of the Irtish from Kras-noyarskoi to Tobolsk.“Between the meridians of Oust-Kamenogorsk and of Semi-polatinsk, the system of the Altaï mountains extends from eastto west, beneath the parallels of 59° and 50°, by a chain of hillsand low mountains, for 160 geographical leagues, as far as thesteppe of the Kirghiz. This range, though of very small im-portance in respect to size and elevation, is highly interesting togeognosy. There does not exist a continuous chain of Kirghizmountains, which, as the maps represent under the names ofAlghidin-tsano or Alghidin-chamo, unites the Ural and theAltaï. Some isolated hills of 500 or 600 feet high, groups ofsmall mountains, which, like the Semi-tau near Semipolatinsk,rise abruptly to the height of 1000 or 1200 feet above theplains, deceive the traveller who is not accustomed to measurethe inequality of the soil; but it is not less remarkable thatthese clusters of hills and small mountains have been raisedacross a furrow which forms this line of division of the watersbetween the affluents of the Saras, or to the south in the steppe,and those of the Irtish to the north: a fissure which followsuniformly, as far as the meridian of Sverinagolovskoy, the samedirection for sixteen degrees of longitude.“In the line of division of the waters between the Altaï andthe Ural, between the 49th and 50th parallels, is observable aneffort of nature, a kind of attempt of subterranean energy, toforce up a chain of mountains; and this fact recalls powerfullythe similar appearances I remarked in the new continent.“But the non-continued range of low mountains and hills ofcrystallized rocks, by which the system of the Altaï is prolongedto the west, does not reach the southern extremity of the Ural,a chain which, like that of the Andes, presents a long wall run-ning from north to south, with metallic mines on its easternside: it terminates abruptly under the meridian of Sverinogov-|232| loskoy, where geographers are accustomed to place the Alghinicmountains, the name of which is entirely unknown by theKirghiz of Troitsk and of Orenburg.“II. System of the Tëen-Shan.—Their mean latitude is 42°.Their culminating point is perhaps the mass of mountain re-markable by its three peaks, covered with eternal snows, andcelebrated under the name of Bokhda-ula, or ‘Holy Mountain,’in the Mongol-Calmuc tongue; which has caused Pallas to giveto the whole chain the denomination of Bogdo. From theBokhda-ula, the Tëen-shan runs easterly towards Barkoul,where, to the north of Hami, it sinks abruptly, and spreads it-self to the level of the high desert called the Great Gobi, orShamo, which extends south-west and north-east, from Kwa-chow, a town of China, to the sources of the Argun. MountNomkhun, to the north-west of the Sogok and the Sobo, littlelakes of the steppe, denotes perhaps by its position, a slightswell, an angle in the desert; for after an interruption of atleast ten degrees of longitude, there appears, a little more to thesouth than the Tëen-shan, in my opinion, as a continuation ofthis system, at the great bend of the Hwang-ho, or YellowRiver, the snowy chain of the Gajar, or Yn-shan, which runslikewise from west to east, under the parallels of 41° and 42°,consequently to the north of the country of Ordos.“Let us now return to the neighbourhood of Toorfan andthe Bokhda-ula, and follow the western prolongation of thesecond system of mountains; we shall perceive that it extendsbetween Gulja (Ele), the place whither the Chinese governmentexiles criminals, and Kucha; then between Temoortu, a largelake, the name of which signifies ‘ferruginous water,’ and Aksu,to the north of Cashgar, and runs towards Smarkand. Thecountry comprised between the first and second systems of moun-tains, or between the Altaï and the Tëen-shan, is closed on theeast, beyond the meridian of Peking, by the Khingkhan-ula, amountainous crest which runs SSW. and NNE.; but to thewest it is entirely open on the side of the Chwei, the Sarasu andthe lower Sihoon. In this part there is no transverse ridge,provided, at least, we do not regard as such the series of eleva-tions which extend north and south, to the west of lake Zaisang,across the Targabatay, as far as the north-eastern extremity of|233| the Ala-tau *, between lakes Balkash and Alak-tugulnoor, andthen beyond the course of the Ele, to the eastward of the Te-moortu-nor (between lat. 44° and 49°), and which present theappearance of a wall occasionally interrupted on the side of theKirghiz steppe.It is quite otherwise with the portion of Central Asia, whichis bounded by the second and third systems of mountains, theHimalaya and Kwan-lun. In fact, it is closed to the west in avery evident manner by a transverse ridge, which is prolongedfrom south to north, under the name of Bolor or Beloortagh †This chain separates Little from Great Bucharia, and fromCashgar, Badakshan and the Upper Jihoon or Amoodaria. Itssouthern portion, which connects with the system of Kwan-lunmountains, forms, according to the denomination used by theChinese, a part of the Tsung-ling. To the north it joins thechain which passes to the north-west of Cashgar, and bears thename of the defile of Cashgar (Cashgar-divan or davan), ac-cording to the narrative of Nasaroff, who, in 1813, travelled as

* This is a name which has occasioned much confusion. The Kirghiz,particularly those of the grand horde, give the title of Ala-tagh (Alatau,‘speckled mountains’) to a series of elevations extending from west to east,under the parallels of 43° 30′ to 45°, from the Upper Sihoon (Syr-daria orJaxartes), near Tonkat, towards lakes Balkashi and Temoortu. The easternportion of the Ala-tau rises considerably at the great sinuosity made by theSihoon to the north-west, and connects with the Kara-tau (‘Black Moun-tain’) at Taras or Turkestan. The natives likewise give the name of Ala-tau to the mountains to the south of the Tarbagatay between lakes Ala-kul,Balkashi, and Temoortu. Is it from these denominations that geographershave been in the habit of calling the whole second system of mountains thatof Tëen-shan, Alak or Ala-tau? The Oolug-tagh, or ‘Great Mountain,’named on some maps Oulug-tag Oolu-tau, and Ooluk-tagh, must not be con-founded with the Ala-tau or Ala-taghi.† According to M. Klaproth, this transversal ridge is named in OuigoorBoolyt-tagh, ‘Cloudy Mountain’, on account of the extraordinary rains whichfall uninterruptedly in this latitude during three months. West of thistransverse ridge of Beloor, is the station of Pamir, nearly under the parallelof Cashgar. Marco Polo has named after this station a table-land, of whichmodern geographers have made sometimes a chain of mountains, sometimesa province situated farther to the south. This district is still interesting tothe naturalist, on account of the celebrated Venetian Traveller having firstobserved there a fact, which has so often occurred in my experience, at con-siderable elevations, in the New World, namely, that it is extremely difficultto light and to keep fire in there.|234| far as Kokand. Between Kokand, Dervazeh and Hissa, conse-quently between the still unknown sources of the Sihoon andAmoo-daria, the Tëen-shan rises previous to sinking again inthe Khanat of Bokhara, and presents a group of lofty moun-tains, several summits of which, such as the Takt-i-Suleyman,the crest called Terek and others, are covered with snow evenin summer. Farther to the east, on the road which runs fromthe western bank of lake Temoortu to Cashgar, the Tëen-shandoes not appear to me to attain so great an elevation; at leastno mention is made of snow in the itinerary from Semipolatinskto Cashgar. The road passes to the east ward of lake Balkashi,and to the westward of lake Yssi-kul or Temoortu, and traversesthe Narun or Narym, an affluent of the Sihoon. At 105 versts tothe south of the Narun, it goes over Mount Rovatt, which ispretty high, and about fifteen versts wide; it has a large cavern,and is situated between the At-bash, a small river, and the littlelake of Chater-kul. This is the culminating point previous toarriving at the Chinese post placed to the south of the Aksu, asmall river of the steppe, the village of Artush, and Cashgar. Thiscity, built on the banks of the Aratumen, contains 15,000 housesand 80,000 inhabitants, but is yet smaller than Samarkand.The Cashgar-davan * does not appear to form a continuous wall,but to offer an open passage at several points. M. Gens ex-pressed to me his surprise that none of the numerous itinerariesof Bokharians which he has collected, make mention of a loftychain of mountains between Kokand and Cashgar. The greatsnowy mountains seem not to reappear till east of the meridianof Aksu, for these same itineraries mention Jeparleh †, a glacier

* The terms davan in Oriental-Turki, dabahn in Mongol, and dabaganin Manchoo, denote not a mountain, but a pass in a mountain; Cashgar da-van, therefore, signifies only the pass across the mountains to Cashgar.—Klaproth.† This is the Moosar-tag, or glacier between Ele and Kucha. The icewith which it is sheeted gives it the appearance of a mass of silver. A road,called Mussar-dabahn, cut through these glaciers, leads from the SW. to the N.,or, to speak more accurately, from Little Bucharia to Ele. The following is adescription of this mountain by a modern Chinese geographer: ‘To the northis the post station of Gakhtsa-karkai, and to the south that of Tamga-tash,or Terma-Khada; they are distant from each other 120 le. On proceeding|235| covered with perpetual snow, on the Kura road, on the banksof the Ele at Aksu, nearly half-way between the warm springsof Arashan to the north of Kanjeilao, a Chinese station, andthe advanced post of Tamga-tash.The western prolongation of the Tëen-shan or Mooz-tag, asthe editors of the Memoirs of Sultan Baber called it by pre-

to the south, after quitting the former, the view extends over a vast spacecovered with snow, which in winter is very deep. In summer, on the top ofthe ice, snow and marshy places are found. Men and cattle follow the wind-ing paths at the side of the mountain. Whoever is so imprudent as to ven-ture upon this sea of snow is irrecoverably lost. After traversing upwards oftwenty le, you reach the glacier, where neither sand, trees, nor grass can beseen: the most terrifying objects are the gigantic rocks formed of massesof ice heaped upon one another. When the eye dwells upon the intervalswhich separate these masses of ice, a gloomy chasm appears, into which thelight never penetrates. The sound of the water rushing beneath the ice re-sembles the report of thunder. Carcasses of camels and horses are scatteredhere and there. In order to facilitate the passage, steps have been cut inthe ice, to ascend and descend, but they are so slippery that they are ex-tremely dangerous. Too frequently travellers find their graves in these pre-cipices. Men and cattle walk in file, trembling with alarm, in these inhos-pitable tracts. If night surprise the traveller, he must seek shelter under alarge stone; if the night happen to be calm, very pleasing sounds are heard,like those of several instruments combined; it is the echo which repeats thecracking noise produced by the breaking ice. The road, which is pursuedthe day before, is not always that which it is convenient to follow the nextday. At a distance, to the west, a mountain, which has been hitherto inac-cessible, displays its steep and icy summits. The halting-place of Tamga-tash is eighty le from this place. A river, called Moossur Gol, rushes withfrightful impetuosity from the edges of the ice, flows to the south-east, andjoins the Erghew, which falls into lake Lob. Four days’ journey to thesouth of Tamga-tash, is an arid plain, which does not produce the smallestplant. At eighty or ninety le further off, gigantic rocks still recur. Thecommandant of Ushi sends every year one of his officers with oblations tothis glacier. The formula of the prayer recited on this occasion is trans-mitted from Peking by the Tribunal of Rites. Ice is found along the wholecrest of the Tëen-shan, if it is traversed lengthwise; but, on the contrary,if it is crossed from north to south, that is in its width, ice is found only ina space of a few le. Every morning ten men are employed in the pass ofMussar-tag, in cutting steps for ascending and descending; in the afternoonthe sun has either melted them or rendered them extremely slippery. Some-times the ice gives way under the feet of the travellers, and they are in-gulfed, without a hope of ever seeing day-light again. The Mohamedansof Little Bucharia sacrifice a ram previous to traversing these mountains.Snow falls there throughout the year: it never rains.—Klaproth.|236| eminence, deserves a particular notice. At the point wherethe Beloor-tag joins the right angle of the Mooz-tag, or tra-verses as a vein this great system, the latter continues itscourse without interruption from east to west, under the deno-mination of Asferah-tag, to the south of the Sihon, towards Kho-jand and Urateppeth, in Ferghana. This chain of Asferah,which is covered with perpetual snow, and is improperly calledthe chain of Pamer, separates the sources of the Sihon (Jaxartes)from those of the Amoo (Oxus); it turns to the south-west,nearly in the meridian of Khojand, and in this direction iscalled, as far as near Samarkand, Ak-tag (“White or SnowyMountain”), or Al-botom. Farther to the west, on the smilingand fertile banks of the Kohik, commences the great dip ordepression of land, comprehending Great Bucharia, the coun-try of Maveralnahar, which is so low, and where the highly-cul-tivated soil and the wealth of the towns attract periodically theinvasions of the people of Iran, Candahar, and Upper Mon-golia; but beyond the Caspian Sea, nearly in the same latitude,and in the same direction as the Tëen-shan, appears theCaucasus, with its porphyritic and trachytic rocks. One is in-clined, therefore, to regard it as a continuation of the rent,in the form of a vein, on which the Tëen-shan rises in the east,just as, to the west of the great group of the mountains ofAzerbaijan and Armenia, is observable, in Taurus, a continua-tion of the action of the fissure of the Himalaya and the HinduCoosh. It is thus that, in a geognostic sense, the disjointedmembers of the mountains of Western Asia, as Mr Ritter, inhis excellent View of Asia, calls them, connect themselves withthe forms of the land in the east.III. The System of the Kwan-lun, or Koolkun, or Tartash-davan, enters Khoten (Elechi *), where Hindu civilization andthe worship of Buddha penetrated 500 years before it reached

* The position of Knoten is very incorrectly laid down in all the maps.Its latitude, according to the astronomical observations of the MissionariesFelix d’Arocha, Espinha, and Hallerstein, is 37° 0′; the longitude 35° 52′ W.of Peking. This longitude determines the mean direction of the Kwan-lun|237| Tibet and Ladak, between the group of mountains of Kookoo-noor and Eastern Tibet, and the country called Kachi.This system of mountains commence westward of the Tsung-ling (“Onion or Blue Mountains”), upon which M. AbelRémusat has diffused so much light in his learned History ofKhoten. This system connects itself, as already observed, withthe transverse chain of Bolor; and according to the Chinesebooks, forms the southern portion of it. This quarter of the globe,between Little Tibet and Badakshan, abounding in rubies,lazulite, and turquoise, is very little known; and, according torecent accounts, the table-land of Khorasan, which runs to-wards Herat, and bounds the Hindu-Kho or Hindu-Coosh tothe north, appears to be a continuation of the system of theKwan-lun to the west, rather than a prolongation of the Hima-laya, as commonly supposed. From the Tsung-ling, the Kwan-lun or Koolkun runs from west to east, towards the sources ofthe Hwang-ho (Yellow River), and penetrates, with its snowypeaks into the Chinese province of Shen-se. Nearly in themeridian of these sources, rises the great cluster of mountains oflake Kookoo-noor, a cluster which supports itself, on the north,against the snowy chain of the Nan-shan, or Ki-lian-shan, ex-tending also from west to east. Between the Nan-shan and theTëen-shan, on the side of Hami, the mountains of Tangoutbound the edge of the high desert of Gohi or Shamo, whichstretches from south-west to north-east. The latitude of themiddle portion of the Kwan-lun is about 35° 30′.IV. System of the Himalaya,—This separates the valleys ofCashmer (Serinagur) and Nepal from Butan and Tibet; to thewest, it stretches by Jevahir, to 4026 toises (26,420 feet); tothe east, by Dhavalaghiri, to 4390 (28,809 feet) of actualheight above the level of the sea: it runs generally in a direc-tion from NW. to SE., and consequently is not parallel withthe Kwan-lun; it approaches it so nearly, in the meridian ofAttock and Jellalabad, that between Cabul, Cashmer, Ladak,and Badakshan, the Himalaya seems to form only a single massof mountains with the Hindu-Kho and the Tsung-ling. Inlike manner, the space between the Himalaya and the Kwan-lun is more shut up with secondary chains and isolated masses|238| of mountains, than the table-lands between the first, second, andthird systems of mountains. Consequently, Tibet and Kachicannot properly be compared, in respect to their geognosticconstruction, with the elevated longitudinal valleys *, situatedbetween the chain of the eastern and western Andes, for ex-ample, with the table-land which encloses the lake of Titicaca,a correct observer of which (Mr Pentland) found that its ele-vation above the sea was 1986 toises (13,033 feet). Neverthe-less, it must not be represented that the height of the table-landbetween the Kwan-lun and the Himalaya, as well as in all therest of Central Asia, is equal throughout. The mildness of thewinters, and the cultivation of the vine †, in the gardens ofH’lassa, in the parallel of 29° 40′,—facts ascertained by the ac-counts published by M. Klaproth and the ArchimandriteHyacinth,—proclaim the existence of deep valleys and circularhollows. Two considerable rivers, the Indus and the Zzambo(Sampoo ‡), denote a depression in the table-land of Tibet, tothe north-west and south-east, the axis of which is found nearlyin the meridian of the gigantic Javahir, the two sacred lakes ofManassoravara and Ravana Hrada, and Mount Caīlasa, or

* In the Andes, I found that the mean height of the longitudinal val-ley between the Eastern and Western Cordilleras, from the cluster of moun-tains of Los Robles, near Popayan, to that of Pasco, as well as those in 2°20′ N. Lat. to 10° 30′ S. Lat., was about 1500 toises (9843 feet). The table-land, or rather longitudinal valley of Tiahuanaco, along the Lake of Titicaca,the primitive seat of Peruvian civilization, is more elevated than the Peakof Teneriffe. However, according to my experience, it cannot be assertedgenerally that the absolute height to which the bottom of the longitudinal val-leys appears to have been raised by subterranean force, augments with theabsolute height of the neighbouring chains. In like manner, the elevationof isolated chains above the valleys is very various, showing that at thefoot of the chain the raised plain is elevated at the same time, or has pre-served its ancient level.† The cultivation of plants, whose vegetable life is almost limited tothe duration of summer, and which, despoiled of leaves, remain benumbed du-ring winter, may be accounted for by the influence which vast table-landsexert upon the radiation of heat; but it is not the same with the lessrigour of winters, when we refer to elevations of 1800 to 2000 toises(11,812 to 13,125 feet) at six degrees to the north of the equinoctial zone.‡ The researches of M. Klaproth have proved that this river, which isentirely separated from the system of the Brahmaputra, is identical withthe Irrawaddy of the Burmese empire.|239| Cailas, in Chinese O-new-ta, and in Tibetan Gang-dis-ri. Fromthis nucleus springs the chain of Kara-korum-padisha, whichruns to the north-west, consequently to the north of Ladak, to-wards the Tsung-ling; and the snowy chains of Hor (Khor)and Zzang, which runs to the east. That of Hor, at its north-western extremity, connects itself with the Kwan-lun; its course,from the eastern side, is towards the Tangri-noor (“Lake ofHeaven”). The Zzang, farther to the south than the chain ofHor, bounds the long valley of the Zzangbo, and runs fromwest to east, towards the Nëen-tsin-tangla-gangri, a very loftysummit which, between H’lassa and lake Tangri-noor (impro-perly called Terkiri), terminates at Mount Nom-shun-ubashi.Between the meridians of Ghorka, Katmandu, and H’lassa, theHimalaya sends out to the north, towards the right bank, orthe southern border of the valley of the Zzang-bo, severalbranches covered with perpetual snow. The highest is Yaria-shamboy-gangri, the name of which, in Tibetan, signifies “thesnowy mountains in the country of the self-existing deity.”This peak is to the westward of lake Yamruk-yumdzo, whichour maps call Palteh *, and which resembles a ring, being al-most filled by an island.If, availing ourselves of the Chinese writings which M.Klaproth has collected, we follow the system of the Himalayatowards the east, beyond the English territories in Hindustan,we perceive that it bounds Assam to the north, contains thesources of the Brahmaputra, passes through the northern partof Ava, and penetrates into the Chinese province of Yun-nan,where, to the westward of Yung-chang, it exhibits sharp andsnowy peaks; it turns abruptly to the north-east on the confinesof Ho-kwang, of Keang-si, and of Fuh-kien, and extends withits snowy summits near to the ocean, where we find, as if it wasa prolongation of this chain, an island (Formosa), the moun-tains of which are covered with snow during the greatest part ofthe summer, which shows an elevation of at least 1900 toises(12,469 feet). Thus we may follow the system of the Hima-laya, as a continuous chain, from the Eastern Ocean, and track

* There can be no doubt that Palteh is derived from Bhaldi, the Tibetanname of a town a little to the north, which has been corrupted by the Chineseinto Peiti or Peti—Klaproth.|240| it by the Hindu-Coosh, across Candahar and Khorasan; andlastly as far as the Caspian Sea in Azerbaijan, through an ex-tent of seventy-three degrees of longitude, half that of theAndes. The western extremity, which is volcanic, but coveredlikewise with snow to Demavend, loses the peculiar characterof a chain in the cluster of the mountains of Armenia, con-nected with the Sangalu, the Bingheul, and Cashmer-dag, loftysummits in the pashalic of Erzeroum. The mean direction ofthe system of the Himalaya is N. 55° W.(To be continued.)|145|

On the Chains of Mountains and Volcanoes of Central Asia.By Baron A. Von Humboldt. (Concluded from preced-ing Volume, p. 240.)

* The astronomical geography of Inner Asia is still very confused, becausethe elements of the observations are not known, merely the results.† A series of barometrical levels continued throughout a very severe win-ter, during the expedition of Colonel Berg, from the Caspian Sea to the west-ern shore of Lake Aral, at the Bay Mertvoy Kultuk, by Captains Duhameland Anjou, has demonstrated that the level of Lake Aral is 117 English feetabove that of the Caspian Sea.|147| square leagues, and which lies between the Kooma, the Don, theVolga, the Yak, the Obsheysyrt, lake Aksakal, the Lower Sihon,and the Khanat of Khiva, upon the shores of the Amoo-daria,is situated below the level of the ocean. The existence of thissingular depression has been the object of laborious barometricalobservations of levels between the Caspian Sea and the BlackSea, by MM. Parrot and Engelhardt; between Orenburg andGouriev at the mouth of the Yaik, by MM. Helmersen andHoffmann. This very low country is abundant in tertiary forma-tions, whence proceeds melaphyre, and debris of scorified rocks,and offers to the geognostic inquirer, from the constitution of itssoil, a phenomena hitherto unique in our planet. To the southof Baku, and in the Gulf of Balkan, this aspect is materiallymodified by volcanic forces. The Academy of Sciences of StPetersburgh has recently complied with my solicitations to getdetermined by a series of stations of barometric levels uponnorth-eastern edge of this basin, upon the Volga between Kamy-shin and Saratov, upon the Yaik between the Obsheysyrt, Oren-burg, and the Uralsk, upon the Yemba and beyond the hills ofMougojar, by which the Ural extends itself towards the southon the side of lake Aksakal and towards Sarasu, the position ofa geodœsic line, uniting all the points at the level of the surfaceof the ocean.I have referred already to the hypothesis, according to whichthis great depression of the land of Western Asia was formerlycontinued as far as the mouth of the Ob and the Frozen Sea, bya valley traversing the desert of Kara-koum and the numerousgroups of oases in the steppes of the Kirghiz and Baraba. Itsorigin appears to me to be more ancient than that of the Uralmountains, the southern prolongation of which may be traced inan uninterrupted course from the table-land of Gaberlinsk toOustoort, between lake Aral and the Caspian Sea. Would nota chain, whose height is so inconsiderable, have entirely dis-appeared if the great rent of the Ural had not been formedsubsequently to this depression? Consequently, the period ofthe sinking of Western Asia coincides rather with that of therising of the table-land of Iran, that of Central Asia, the Hima-laya, the Kwan-lun, the Tëen-shan, and all the old systems ofmountains running from east to west; perhaps also with the|148| period of the upraising of the Caucasus and the cluster of moun-tains of Armenia and Erzeroum. No part of the earth, noteven excepting South Africa, presents a mass of land so extensive,and elevated to so great a height, as that in Central Asia. Theprincipal axis of this upraising, which probably preceded theeruption of the chains from the rents running from east to west,as in the direction of S. W. and N. E., from the group of moun-tains between Cashmer, Badakshan, and the Tsung-ling in Tibet,where are situated the Caïlasa, and the sacred lakes*, as far asthe snowy summits of the Inshan and Khingkan†. The eleva-tion from below of so enormous a mass would suffice to producea sinking or hollow which, even at the present day, is perhapsnot half filled with water, and which, since it was formed, hasbeen so modified by the action of subterranean forces, that, ac-cording to the traditions of Tartars, collected by Professor Eich-wald, the promontory of Absheron was formerly united by anisthmus with the opposite coast of the Caspian Sea in Turco-mania. The great lakes, which have been formed in Europe

* The lakes Manasa and Ravan Hrad. Manasa, in Sanscrit, signifies“spirit.” Manasa-vara is the easternmost of these two lakes: its name meansliterally “the most perfect of honourable lakes.” The westernmost lake isnamed Ravanah Hrad, or “Lake of Ravana,” after the celebrated hero of theRamayana.—Bopp.† This direction of the axis of elevation from the S. W. to the N. E. isagain found beyond the 55th degree of latitude, in the space comprised be-tween Western Siberia, a low country, and Eastern Siberia, a country full ofchains of mountains: this space is bounded by the meridian of Irkutsk, theFrozen Sea, and the Sea of Okotsk. Dr Erdman has discovered among theAldan mountains, at Allakh-yuma, a peak 5000 feet high. To the north ofthe Kwan-lun, the chain of Northern Tibet, and to the west of the meridianof Peking, the portions of elevated land most important in respect to the ex-tent and height, are the following:—1. To the east of the cluster of the Kook-oonoor, the space between Toorfan, Tangut, the great sinuosity of theHoang-ho, Garjan, and the chain of the Khing-khan, a space which compre-hends the great desert of Gobi. 2. The table-land between the snowy moun-tains of Khangai and Tangnu, and between the sources of the Yeniseï, theSelengga and the Amoor. 3. To the west of the district watered by the uppercourse of the Oxus (Amou), and of the Jaxartes (Sihoon); between Fyzabad,Balkh, Samarkand and the Ala-tau near Turkestan, to the westward of theBolor (Beloot-tag). The upraising of this transverse ridge has produced inthe soil of the great longitudinal valley of the Tëen-shan-nar-lu, between thesecond and third systems of mountains from east to west, or between theTëen-shan and the Kwanlun, a counter-slope from west to east, whilst in thelongitudinal valley of the Tëenshan-pe-lu in Zungaria, between the Tëen-shanand the Altaï, a general declivity is observable from east to west.|149| at the foot of the Alps, are a phenomenon analogous to the ca-vity in which the Caspian Sea is situated, and owe in the samemanner their origin to a sinking of the land. We shall soonsee that it is principally in the compass of this hollow, conse-quently in the space where the resistance was least, that recenttraces of volcanic action are apparent.The position of mount Aral-toube, which formerly emittedfire, of the existence of which I became aware from the itine-raries of Colonel Gens, becomes more interesting when we com-pare it with that of the volcanoes of Pechan and Ho-tcheou, onthe northern and southern sides of the Tëen-shan, with that ofthe solfatara of Ouroumtsi, and with that of the adjoining chasmof lake Darlai, which exhales ammoniacal vapours. The re-searches of MM. Klaproth and Rémusat acquainted us withthis last fact upwards of six years ago.The volcano situated in about the latitude of 42° 25′ or 42° 35′,between Korgos, on the banks of the Ele, and Kouche, in LittleBucharia, belongs to the chain of the Tëen-shan: perhaps itmay be on the northern face, three degrees to the eastward oflake Yssi-kul or Tremoortu. Chinese authors call it Pïh-shan(“White Mountain”), Ho-shan, and Aghi (“Fiery Moun-tain”)*. It is not known with certainty whether the name of Pĭh-shan implies that its summit reaches the line of perpetual snow,which the height of this mountain would determine, at least theminimum; or whether it merely denotes the glittering hue of a

* The details given M. Klaproth (Tabl. Hist. de l’Asie, p. 110; Mem. re-latifs á l’Asie, t. ii. p. 358) are the most complete, and derived principallyfrom the history of the Ming dynasty. M. Abel-Rémusat (Journ. Asiat. t. v.p. 45; Descrip. de Khotan, t. ii. p. 9), has added more in the Japanese trans-lation of the grand Chinese Encyclopedia. The root ag, which is found inthe word Aghi, according to M. Klaproth, signifies “fire” in Hindustani.To the south of Pih-shan, in the neighbourhood of Khoten, belonging to theTëen-shan-nar-lu, there can be no doubt that, prior to our era, Sanscrit wasspoken, or a language possessing a strong analogy with it: but in Sanscrit aflaming mountain is called Agni-ghri. According to M. Bopp, Aghi is not aSancrit word.—HumboldtThe root ag, which is found in the word Aghi, signifies “fire” in all thedialects of Hindustan; this element is ag in Hindustani, agh in Mahratta,and the form of agi is still preserved in the dialect of the Punjab. The wordagni, by which “fire” is commonly designated in Sanscrit, belongs to the sameroot, as well as agun in Bengalee, ogun in Russian, and the ignis of theLatins.—Klaproth.|150| peak covered with saline substances, pumice-stone, and volcanicashes in decomposition. A Chinese author of the seventh cen-tury says: At 200 le, or fifteen leagues, to the north of the cityof Kwei-chow (now Koutche), in about the latitude of 41° 37 andlongitude 80° 35′ E., according to the astronomical determina-tion of the missionaries made in the country of the Eleuths, risesthe Pechan, which emits fire and smoke without interruption.It is from thence sal ammoniac is brought; upon one of the de-clivities of the Fiery Mountain (Ho-tcheou), all the stones burn,melt, and flow to a distance of some tens of le. The fused mass *hardens as it becomes cold. The natives use it in disorders †as a medicine: sulphur is also found there.M. Klaproth observes, that this mountain is now called Kha-lar ‡, and that, conformably to the account given by the Bok-hars, who bring to Siberia sal-ammoniac (called nao-sha inChinese, and nōshāder in Persian), the mountains to the south ofKorgos is so abundant in this species of salt, that the nativesfrequently employ it as a means of paying their tribute to theEmperor of China. In a recent Description of Central Asia,

* The history of the Chinese dynasty Tang, speaking of the lava from thePih-shan, states that it ran like liquid fat.—Klaproth.† This is not lava, but the saline particles which appear in the form of anefflorescence on its surface.‡ The Pih-shan of the ancient Chinese, at present has the Turk name ofEshik-bosh; Eshik is a species of goat, and bash signifies “head.” Sulphuris produced there in abundance. The Eshik-bash belongs to the elevatedmountains, which, in the time of the Wei dynasty (the third century) bound-ed, to the north-west, the kingdom of Kwei-tsu (Ku-cha); it is the Aghi-shan under the Suy dynasty (in the early moiety of the seventh century).The history of this dynasty relates that this mountain always shewed fireand smoke, and that sal-ammoniac was obtained there. In the description ofthe western country, which forms a part of the history of the Tang dynas-ty, we find that the mountain in question was then called Aghi-teen-shan(which may be translated “mountain of fields of fire”), or Pih-shan (“whitemountain”), that it was to the north of the city of Ilolo, and that it emittedperpetual fire. Ilolo (or perhaps Irolo, Ilor, or Irol) was then the residenceof the King of Kwei-tsu.The Eshik-bash is to the north of Ku-cha, and 200 leagues to the west ofthe Kan-tengri, which forms part of the chain of the Teen-chan. The Eshik-bash is very large, and much sulphur and sal-ammoniac is even now col-lected there. It gives birth to the river Eshik-bash-gol, which flows to thesouth of the city of Kucha, and falls, after a course of 200 le, into theErghew.|151| published at Peking in 1777, we find the following statement:—“ The province of Ku-cha produces copper, saltpetre, sul-phur, and sal-ammoniac. The latter article comes from an am-moniac mountain to the north of the city of Koutche, which isfull of chasms and caverns. These apertures in spring, sum-mer, and autumn, are filled to such a degree, that, during thenight, the mountain appears illuminated by thousands of lamps.No one is then able to approach it. In winter alone, when thevast quantity of snow has extinguished the fire, the natives areable to labour in collecting the sal-ammoniac, for which purposethey strip themselves quite naked. The salt is found in ca-verns, in the form of stalactites, which renders it difficult to bedetached.” The name of Tartarian salt, formerly given incommerce to this salt, ought to have long ago directed attentionto the volcanic phenomena of Central Asia.M. Cordier, in his letter to M. Abel Rémusat, “on the ex-istence of two burning volcanoes in Central Asia,” calls Pechana solfatara like that of Puzzuoli. In the state in which it isdescribed in the work cited farther back, the Pechan mightwell deserve only the name of an extinct volcano, although theigneous phenomena are wanting in the solfataras I have seen:such as those of Puzzuoli, the crater of the Peak of Teneriffe,the Rucu-pichincha, and the volcano of Jorullo; but passages inmore ancient Chinese historians, who relate the march of the ar-my of the Heung-nus, in the first century of our era, speak ofmasses of rocks in fusion flowing to the distance of some miles:so that it is impossible, in these expressions, not to understanderuptions of lava. The ammoniac mountain between Koutcheand Korgos has also been a volcano, in activity, in the strictestsense of the word: a volcano which emitted torrents of lava inthe centre of Asia, 400 geographical leagues from the CaspianSea to the west, 433 from the Frozen Sea to the north, 504from the Great Ocean to the east, and 440 from the Indian Oceanto the south. This is not the place to discuss the question rela-tive to the influence of the proximity of the sea on the action ofvolcanoes; I merely solicit attention to the geographical posi-tion of the volcanoes of Inner Asia, and their reciprocal rela-tions. The Pechan is distant from 300 to 400 leagues fromall the seas. When I returned from Mexico, some celebrated|152| mineralogists expressed their astonishment when they heard mespeak of the volcanic eruption of the plain of Jorullo, and of thevolcano of Popocatepetl, as still in activity: although the formeris only thirty leagues from the sea, and the latter forty-threeleagues. Gebel Koldaghi, a conical and smoking mountain ofKordofan, of which Mr Rüppel was told at Dongola, is 150leagues from the Red Sea, and this distance is but a third ofthat at which the Pechan, which for 1700 years has emittedtorrents of lava, is situated from the Indian Ocean. The hy-pothesis, conformably to which the Andes present no volcano inactivity in those parts where the chain recedes from the sea, iswithout foundation. The system of mountains of the Caraccas,which run from east to west, or the chain of the coast of Vene-zuela, is shaken by violent earthquakes, but has no longerapertures which are in permanent communication with the in-terior of the earth, and which discharge lava, than the chain ofthe Himalaya, which is little more than 100 leagues from theGulf of Bengal, or the Ghauts, which may almost be termed acoast-chain. Where trachyte has been unable to penetrateacross the chains when they have been elevated, they discoverno rents; no channels are opened, whereby the subterraneanforces can act in a permanent manner at the surface. The re-markable fact of the proximity of the sea wherever volcanoesare still in activity,—a fact which, in general, is not to be de-nied,—seems to be accounted for less by the chemical agencyof the water, than by the configuration of the crust of the globe,and the deficiency of resistance, which, in the vicinity of mari-time basins, the upraised masses of the Continent oppose toelastic fluids, and to the efflux of matters in fusion in the interiorof our planet. Real volcanic phenomena may occur, as in theold country of the Eleuths, and at Toorfan, to the south of theTëen-shan, wherever, owing to ancient resolutions, a fissure isopened in the crust of the globe at a distance from the sea. Thereason why volcanoes in activity are not more rarely remotefrom the sea, is merely because, wherever an eruption has beenunable to force itself through the declivity of continental massestowards a maritime basin, a very unusual concurrence of cir-cumstances is requisite to permit a permanent communicationbetween the interior of the globe and the atmosphere, and to|153| form apertures, which, like intermittent warm springs, effuse,instead of water, gases and oxidized earths in fusion, in otherwords, lava.To the eastward of Pechan, the “White Mountain” of theEleuths, the whole northern slope of the Tëen-shan presentsvolcanic phenomena: “lava and pumice-stone are seen there,and even considerable solfataras, which are called ‘fiery places.’The solfatara of Ouroumtsi is five leagues in circumference;in winter it is not covered with snow; it is supposed to befull of ashes. If a stone be thrown into this basin, flames issueforth, as well as a black smoke, which continues some time. Birdsdare not fly over these fiery places.” Eastward, sixty leaguesfrom Pechan, is a lake of very considerable extent, the diffe-rent names of which in the Chinese, Kirghiz, and Calmuc lan-guages, signify, “warm salt and ferruginous water.”If we cross the volcanic chain of the Tëen-shan, we findE. S. E. of lake Issikoul (so often mentioned in the itinerarieswhich I have collected), and of the volcano of the Pechan, thevolcano of Toorfan, which may also be called the volcano ofHo-chow (“City of Fire”), for it is very near that city *. M.Abel Rémusat has made particular mention of this volcano inhis Histoire de Khoten, and in his letter to M. Cordier †. Noreference is made to stony masses in fusion (torrents of lava),there, as at Pechan; but “a column of smoke is seen continu-ally to issue; this smoke gives place at night to a flame like thatof a torch. Birds and other animals upon which the light falls,appear of a red colour. The natives, when they go thither tocollect the nao-sha, or sal-ammoniac, put on wooden shoes, forleather soles would be very soon burned.” Sal-ammoniac is pro-cured at the volcano of Ho-tcheou, not only in the form of a crustor sediment, according as it is deposited by the vapours whichexhale it; but Chinese books likewise make mention “of agreenish liquor collected in cavities, which is boiled and evapo-

* Ho-chow, a city, now destroyed, was a league and a half to the east ofToorfan.† M. Rémusat calls the volcano of Pechan, to the north of Koutche, thevolcano of Bishbalik. From the time of the Mongols in China, all the coun-try between the northern slope of the Téen-shan and the little chain of theTarbagatay has been called Bishbalik.|154| rated, and from it sal-ammoniac is obtained in the form of smalllumps like sugar, of extreme whiteness, and perfect purity.”Pechan and the volcano of Ho-tcheou or Tufan are 140leagues apart, in the direction of east and west. About fortyleagues westward of the meridian of Ho-tcheou, at the foot of thegigantic Bokhda-ula, is the great solfatara of Ouroumtsi. At140 leagues north-west of this, in a plain adjoining the banks ofthe Kobok, which flows into the small lake of Darlai, rises ahill, “the clefts of which are very warm, though they do notexhale smoke (visible vapours): the sal-ammoniac, in these cre-vices is sublimed into so solid a coating, that the stone is obligedto be broken in order to get it.”These four places hitherto known, namely, Pechan, Ho-tcheou, Ouroumtsi, and Kobok, which exhibit evident volcanicphenomena, in the interior of Asia, are 130 or 140 leagues tothe south of the point of Chinese Zungaria, where I was at thebeginning of 1829. Aral-toube, the conical and insular moun-tain of Lake Ala-kul, which has been in a state of ignition inhistorical times, and which is mentioned in the itineraries col-lected at Semipolatinsk, is in the volcanic territory of Bishbalik.This insular mountain is situated to the west of the ammoniac-cavern of Kobok, and to the north of Pechan, which stillemits light, and which formerly discharged lava, and at a dis-tance of sixty leagues from each of these two points. FromLake Ala-kul to Lake Zaisang, where the Russian Cossacks ofthe line of the Irtish, exercise the right of fishing, by conni-vance of the Mandarins, the distance is reckoned at fifty-oneleagues. The Tarbagatai, at the foot of which is situatedChoogonchak, a town of Chinese Mongolia, and where DrMeyer, the learned and enterprising companion of M. Lede-bour, fruitlessly essayed, in 1825, to prosecute his researches innatural history, extends to the south-west of Lake Zaisang to-wards the Ala-kul *. We are thus acquainted, in the interior

* I do not wish to express any doubt respecting the existence of the Ala-kul and the Alaktugul-noor lakes, in the vicinity of each other; but it ap-pears singular to me, that the Tartars and Mongols, who traverse these partsso often, and who have been questioned at Semipolatinsk, should only knowthe Ala-kul, and assert that the Alaktugul-noor owes its existence to a con-fusion of names. M. Pansner, in his Russian map of Inner Asia, which maybe implicitly relied on with regard to the country north of the course of the|155| of Asia, with a volcanic territory, the surface of which is upwardsof 2500 square leagues, and which is distant 300 or 400 leaguesfrom the sea: it occupies a moiety of the longitudinal valley situ-ated between the first and second systems of mountains. The chiefseat of volcanic action seems to be in the Tëen-shan. Perhapsthe colossal Bokhda-ula is a trachytic mountain like Chimbora-zo. On the side north of the Tarbagatai and of Lake Darlai,the action becomes weaker; yet Mr Rose and I found whitetrachyte along the south-western declivity of the Altaï, upon abell-shaped hill at Ridderski, near the village of Butach-chikha.On both sides of the Tëen-shan, north and south, violentearthquakes are felt. The town of Aksou was entirely destroyedby a convulsion of this kind at the beginning of the eighteenthcentury. Professor Eversman, of Casan, whose repeated tra-vels have made us acquainted with Bokhara, was told by a Tar-tar, who was a servant of his, well acquainted with the countrybetween Lakes Balkashi and Ala-kul, that earthquakes werevery common there. In eastern Siberia, to the north of the fif-tieth parallel, the centre of the circle of shocks appears to be atIrktusk, and in the deep basin of Lake Baikal, where, on theKiachta road, especially on the banks of the Jeda, and the

Ele, makes the Ala-kul (properly Ala-ghul, or “party-coloured lake”) com-municate with the Alaktugul by five channels. Possibly the isthmus whichseparates these lakes, may be marshy, which causes them to be considered asone. Casim Bek, a professor at Casan, and who is a Persian by birth, insiststhat tugul is a Tartaro-Turkish negation, and that therefore, Altatugul signi-fies “the lake not variegated,” as Ala-tau-ghul implies “the lake of the va-riegated mountain.” Perhaps the names of Ala-kul and Ala-tugul meanmerely “lake near the Ala-tau mountain,” which stretches from Turkestanto Zungaria. The small map published by the English missionaries of theCaucasus, does not contain the Ala-kul; there appears only a group of threelakes, the Balkashi, the Alak-tugul, and the Koorgeh. The hypothesis,however, according to which the vicinity of large lakes produces, in the in-terior of Asia, the same effect upon volcanoes remote from the sea, as theocean, is without foundation. The volcano of Toorfan is surrounded only byinsignificant lakes; and, as it has been already remarked, Lake Temoortu orYsal-kul, which is less than double the extent of the Lake of Geneva, isthirty-three leagues from the volcano of Pih-shan.—Humboldt.The Chinese maps represent the two lakes as one, having a mountain inthe midst. This lake is called Ala-kul, its eastern portion bears the name ofAlak-tugul nor, and its western gulf that of She-bartu-kholay.—Klaproth.|156| Chekoy, basalt is found with olivine, cellular amygdaloid,chabasie, and apophyllite *. In the month of February1829, Irktusk suffered greatly from violent earthquakes;and in the month of April following, convulsions were alsofelt at Ridderski, which were perceived at the bottom of themines, where they were very severe. But this part of theAltaï is the extreme limit of the circle of shocks; farther to thewest, in the plains of Siberia, between the Altaï and the Ural,as well as along the entire chain of the latter, no motion has hi-therto been observed. The volcano of Pechan, the Aral-tou-be, to the westward of the caverns of sal-ammoniac of Kobok,Ridderski, and the portion of the Altaï which abounds in me-tals, are situated for the most part in a direction which butslightly deviates from that of the meridian. Perhaps the Altaïmay be comprehended within the circle of the convulsions of theTëen-shan, and the shocks of the Altaï, instead of coming onlyfrom the east, or from the basin of the Baikal, may also comefrom the volcanic country of Bishbalik. In many parts of thenew continent, it is clear, that the circles of shocks intersect eachother, that is, the same country receives terrestrial convulsionsperiodically on two different quarters.The volcanic territory of Bishbalik is to the eastward of thegreat depression of the old world. Travellers who have journeyedfrom Orenburg to Bokhara, relate that at Sussak in the Kara-tau, which forms with the Ala-tau a promontory to the north ofthe town of Taraz in Turkestan, on the edge of the depression,warm springs spout up. On the south and on the west of the innerbasin we find two volcanoes still in activity; Demavend, whichis visible from Tehran, and the Seyban of Ararat, † which iscovered with vitrified lava. The trachytes, porphyries, and ther-mal springs of the Caucasus are well known. On both sides ofthe isthmus between the Caspian and Black Seas, naphtha springsand volcanoes of mud are numerous. The mud volcano of Ta-man, of which Pallas and Messrs Engelhard and Parrot have

* Dr Hess, associate of the Academy of Sciences of St Petersburgh, whoresided on the borders of the Balkal, and to the south of the lake, from 1826to 1828, gives us reason to expect a geological description of a portion of theremarkable country which he traversed. He frequently observed at Verkh-nei-Oudinsk granite alternating several times with conglomerate.† The height of Ararat, according to Parrot, is 2700 toises (17,718 feet);that of Elbourz, according to Kuppfer, 2560 (16,800 feet) above the level ofthe ocean.|157| described the last fiery eruption, in 1794, from the reports ofTartars, is, according to the very sensible remark of Mr Eich-wald, “a dependency of Baku, and of the whole peninsula ofAbsheron.” Eruptions take place where the volcanic forcesencounter least opposition. On the 27th November 1827, crack-ings and tremblings of the earth, of a violent character, weresucceeded, at the village of Gokmali, in the province of Baku,three leagues from the western shore of the Caspian Sea, by aneruption of flames and stones. A space of ground, 200 toiseslong and 150 wide, burned for twenty-seven hours without in-termission, and rose above the level of the neighbouring soil.After the flame became extinct, columns of water were ejected,which continue to flow till the present hour. I am gratified atbeing enabled to state here, that Mr Eichwald’s periplus of theCaspian Sea, which will soon appear, will contain some very im-portant physical and geological observations, more particularlyupon the connexion of fiery eruptions with the appearance ofnaphtha-springs and strata of rock-salt, on the blocks of calcare-ous rock hurled to considerable distances, on the elevation anddepression of the bed of the Caspian Sea, which still continue;on the passing of black porphyry, partly vitrified and contain-ing garnets (melapyres), through granite, red quartzose por-phyry, very dark calcareous syenite, in the Krasnovodsk moun-tains washed by the bay of the Balkan, to the northward of theancient mouth of the Oxus (Amoo-doria). We shall learn fromthe geognostic description of the eastern shore of the CaspianSea, where the island of Chabekan discovers naphtha-springsthe same as Baku and the isles between this town and Salian,what species of crystallized rocks are hidden beneath the rocksin horizontal strata in the peninsula of Absheron, where the ac-tion of subterranean fire is always felt, and where it has not yetbeen able to reach the open air. The porphyries of the Cauca-sus, which run from W. N. W. to E. S. E., a position and a di-rection which I have already mentioned as the reason of thepresumed connexion of this chain with the rent of the Tëen-shan,discover themselves again, traversing all the rocks nearly to thecentre of the great depression of the old world, to the east of theCaspian Sea, in the mountains of Krasnovodsk and Kurreh.Recent researches and the traditions of the Tartars inform us,that the existence of naphtha springs has always been preceded|158| by fiery eruptions. Several salt lakes on the two opposite shoresof the Caspian Sea have a very elevated temperature; and blocksof rock-salt, traversed by asphaltum, are formed, as Mr Eich-wald remarks with much shrewdness, “by the effect of a suddenvolcanic action, as at Vesuvius,* in the Cordilleras of SouthAmerica and in Azirbidjan, or even under our own observationby the slow but continued action of heat.” M. L. de Buch haslong directed his attention to the connexion of the volcanic for-ces with the masses of anhydrous rock-salt, which traverse sooften and so many formations of horizontal strata.We have already seen that the circles of the terrestrial con-vulsions, of which Lake Baikal or the volcanoes of Tëen-shan arethe centre, do not extend in western Siberia beyond the westerndeclivity of the Altaï, and do not pass the Irtish or the meridianof Semipolantinsk. In the chain of the Ural, earthquakes arenot felt, nor, notwithstanding the rocks abound in metals, do wefind there basalt or olivine, nor trachytes, properly so called, normineral springs. The circle of the phenomena of Azerbidajan,which includes the peninsula of Absheron, or the Caucasus, of-ten extends as far as Kizlar and Astrakhan.It is the same on the border of the great depression in the west.If we direct our observation from the Caucasian isthmus to thenorth and north-west, we come to the country of grand forma-tions in horizontal and tertiary strata, which occupy southernRussia and Poland. In this region, the rocks of pyroxene piercethe red free-stone of Yekaterinoslav, whilst asphaltum andsprings impregnated with sulphurous gas denote other masseshid under the sedimentary deposits. It may also be mention-ed as an important fact, that in the chain of the Ural, whichabounds so much in serpentine and hornblende, and which servesas a boundary between Europe and Asia, a true amygdaloidalformation appear at Griasnushinskaia, towards its southern ex-tremity.We shall content ourselves here with observing, with refer-ence to the ingenious opinions recently promulgated by M. Eliede Beaumont, respecting the relative age and the parallelism of

* In an eruption of this volcano in 1805, M. Guy Lussac and I foundsmall fragments of rock-salt in the lava as it cooled. My Tartar itinerarieslikewise speak of rock-salt in the neighbourhood of a volcanic mountain of theTëen-shan, north of Aksou, between the station of Turpa-gad and MountArbab.|159| systems of contemporary mountains, that, in the interior of Asialikewise, the four grand chains which run from east to west areof a totally different origin from the chains which lie in a direc-tion north and south, or N. 30° W., and S. 30° E. The chainof the Ural, the Bolor, or Beloor-tag, the Ghauts of Malabar,and the Kingkhan, are probably more modern than the chainsof the Himalaya and the Tëen-shan. The systems of differentepochs are not always separated from each other by consider-able spaces, as in Germany, and in the greater part of the newcontinent. Frequently, chains of mountains, or axes of uprais-ing, of dissimilar directions, and belonging to epochs totallydifferent, are nearly approximated by nature; resembling so farthe characters on a monument which, crossing different ways,were engraved at different periods, and carry intrinsic marks oftheir own date. Thus, in the south of France, are seen chainsand undulated swellings, some of which are parallel to the Pyre-nees and others to the western Alps. The same diversity ofgeological phenomena is apparent in the high land of CentralAsia, where isolated portions appear as it were surrounded andenclosed by subdivisions, in parallel lines, of the systems ofmountain.