| Weitere Fassungen |

|

Baron Humboldt’s Last Volume. Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent. Vol. 4. London, 1819 (New York City, New York, 1819, Englisch)

|

|

The gymnotus, or electrical eel (New York City, New York, 1819, Englisch)

|

|

Humboldt’s Travels (London, 1819, Englisch)

|

|

Electrical eels (Cambridge, 1819, Englisch)

|

|

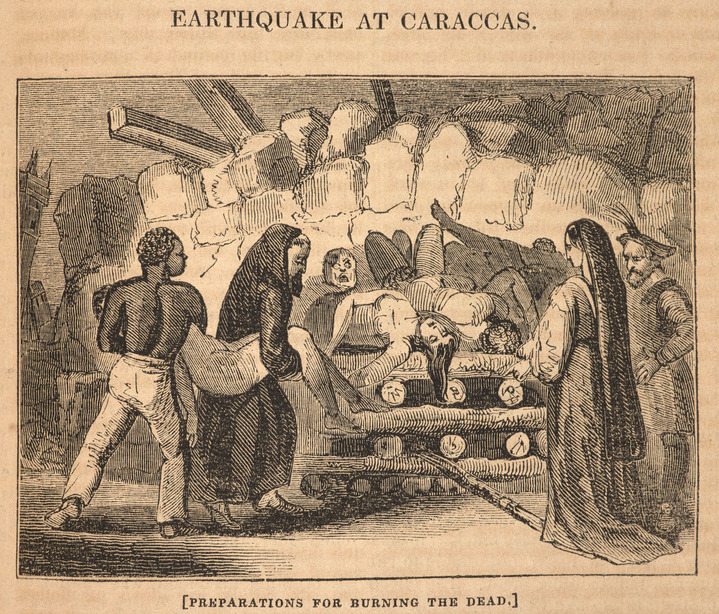

[Earthquake at Caraccas] (Cambridge, 1819, Englisch)

|

|

Account of the Earthquake which destroyed the Town of Caraccas on the 26th March 1812 (Edinburgh, 1819, Englisch)

|

|

Account of the earthquake that destroyed the town of Caraccas on the twenty-sixth march, 1812 (Liverpool, 1819, Englisch)

|

|

Sur les Gymnotes et autres poissons électriques (Paris, 1819, Französisch)

|

|

An Account of the Earthquake in South America, on the 26th March, 1812 (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1820, Englisch)

|

|

[Earthquake at Caraccas] (Hartford, Connecticut, 1820, Englisch)

|

|

Account of the Elecrical Eels, and of the Method of catching them in South America by means of Wild Horses (Edinburgh, 1820, Englisch)

|

|

Observations respecting the Gymnotes, and other Electric Fish (London, 1820, Englisch)

|

|

[Earthquake at Caraccas] (Hallowell, Maine, 1820, Englisch)

|

|

Earthquake in the Caraccas (London, 1820, Englisch)

|

|

Sur les Gymnotes et autres poissons électriques (Paris, 1820, Französisch)

|

|

[Earthquake at Caraccas] (Hartford, Connecticut, 1821, Englisch)

|

|

Earthquake at Caraccas (London, 1822, Englisch)

|

|

Earthquake at the Caraccas (Shrewsbury, 1823, Englisch)

|

|

Electrical eel (Hartford, Connecticut, 1826, Englisch)

|

|

Baron Humboldt’s observation on the gymnotus, or electrical eel (London, 1833, Englisch)

|

|

The gymnotus, or electric eel (London, 1834, Englisch)

|

|

Earthquake at Caraccas in 1812 (Hartford, Connecticut, 1835, Englisch)

|

|

Earthquake at Caraccas (London, 1837, Englisch)

|

|

Electrical eels (London, 1837, Englisch)

|

|

Female presence of mind (London, 1837, Englisch)

|

|

An earthquake in the Caraccas (London, 1837, Englisch)

|

|

An Earthquake (Leipzig; Hamburg; Itzehoe, 1838, Englisch)

|

|

Das Erdbeben von Caraccas (Leipzig, 1843, Deutsch)

|

|

The Gymnotus, or Electrical Eel (Buffalo, New York, 1849, Englisch)

|

|

Anecdote of a Crocodile (Boston, Massachusetts; New York City, New York, 1853, Englisch)

|

|

Battle with electric eels (Goldsboro, North Carolina, 1853, Englisch)

|

|

Anecdotes of crocodiles (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1853, Englisch)

|

|

Das Erdbeben von Caracas (Leipzig, 1858, Deutsch)

|