Digitale Ausgabe

Download

| TEI-XML (Ansicht) | |

| Text (Ansicht) | |

| Text normalisiert (Ansicht) |

Ansicht

| Textgröße | |

| Originalzeilenfall ein/aus | |

| Zeichen original/normiert | |

Abbildungen

Zitierempfehlung

Alexander von Humboldt: „Memoir on a new Species of Pimelodus thrown out of the Volcanoes in the Kingdom of Quito; with some Particulars respecting the Volcanoes of the Andes“, in: ders., Sämtliche Schriften digital, herausgegeben von Oliver Lubrich und Thomas Nehrlich, Universität Bern 2021. URL: <https://humboldt.unibe.ch/text/1806-Memoir_on_a_new_species_of_Pimelodus-1> [abgerufen am 19.04.2024].

URL und Versionierung

|

Permalink: https://humboldt.unibe.ch/text/1806-Memoir_on_a_new_species_of_Pimelodus-1 |

| Die Versionsgeschichte zu diesem Text finden Sie auf github. |

| Titel | Memoir on a new Species of Pimelodus thrown out of the Volcanoes in the Kingdom of Quito; with some Particulars respecting the Volcanoes of the Andes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jahr | 1806 | ||||

| Ort | London | ||||

|

Nachweis in: The Philosophical Magazine 24:96 (Februar–Mai 1806), S. 333–339, Tafel.

|

|||||

|

Entsprechungen in Buchwerken als „Mémoire sur une nouvelle espèce de pimelode, jetée par les volcans du royaume de Quito“, in: Alexander von Humboldt, Recueil d’observations de zoologie et d’anatomie comparée, faites dans l’Océan Atlantique, dans l’intérieur du Nouveau Continent et dans la Mer du Sud pendant les années 1799, 1800, 1801, 1802 et 1803, 2 Bände, Paris: F. Schoell / G. el Dufour 1811 [1812], J. Smith / Gide [1813–] 1833, Band 1, S. 21–25.

|

|||||

| Sprache | Englisch | ||||

| Typografischer Befund | Antiqua; Auszeichnung: Kursivierung, Kapitälchen; Fußnoten mit Asterisken und Kreuzen; Schmuck: Initialen. | ||||

|

Identifikation |

|||||

Statistiken

|

|||||

| Weitere Fassungen | |

|---|---|

|

|

Memoir on a new Species of Pimelodus thrown out of the Volcanoes in the Kingdom of Quito; with some Particulars respecting the Volcanoes of the Andes (London, 1806, Englisch) |

|

|

Volcanic Fish (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1806, Englisch) |

|

|

Particulars respecting the Volcanoes in the Andes, and the Fishes thrown out by them (Edinburgh, 1806, Englisch) |

Memoir on a new Species of Pimelodus thrown out ofthe Volcanoes in the Kingdom of Quito; with someParticulars respecting the Volcanoes of the Andes. ByM. De Humboldt *.

* From Recueil d’Observations de Zoologie et d’Anatomie comparé, 1re livraison.† It would have been of some use to geology had the author here men-tioned whether the stone which he calls basaltes has been submitted tothe action of fire or water; or whether, in addition to the other well knowncharacters of this mineral, it yielded hydrogen gas on distillation, the latterbeing the peculiar characteristic of what is properly denominated basaltes.— Translator. |334| sity of force, it is known, that if the volcanic fire was at agreat depth, the melted lava could neither raise itself to theedge of the crater, nor pierce the flank of these mountains,which to the height of 1400 toises (8971\( \frac{2}{3} \) feet) are fortifiedby high surrounding plains. It appears, therefore, natural,that volcanoes so elevated should discharge from their mouthbut isolated stones, volcanic cinders or ashes, flames, boil-ing water, and, above all, this carburetted argil impregnatedwith sulphur, that is called moya * in the language of thecountry. The mountains of the kingdom of Quito occasionally offeranother spectacle, less alarming, but not less curious to thenaturalist. The great explosions are periodical, and some-what rare. Cotopaxi, Tungurahua, and Sangay, some-times do not present one in twenty or thirty years. Butduring such intervals even these volcanoes will dischargeenormous quantities of argillaceous mud; and, what is moreextraordinary, an innumerable quantity of fish. By acci-dent, none of these volcanic inundations took place the yearthat I passed the Andes of Quito; but the fish vomited fromthe volcanoes is a phænomenon so common, and so gene-rally known by all the inhabitants of that country, that therecannot remain the least doubt of its authenticity. As thereare in these regions several very well informed persons, whohave successfully devoted themselves to the physical sciences,I have had an opportunity of procuring exact information (ren-seignemens) respecting these fishes. M. de Larrea, at Quito,well versed in the study of chemistry, who has formed acabinet of the minerals of his country, has been, above allothers, the most useful to me in these researches. Exa-mining the archives of several little towns in the neighbour-hood of Cotopaxi, in order to extract the epochs of the greatearthquakes, that fortunately have been preserved with care,I there found some notes on the fish ejected from the vol-

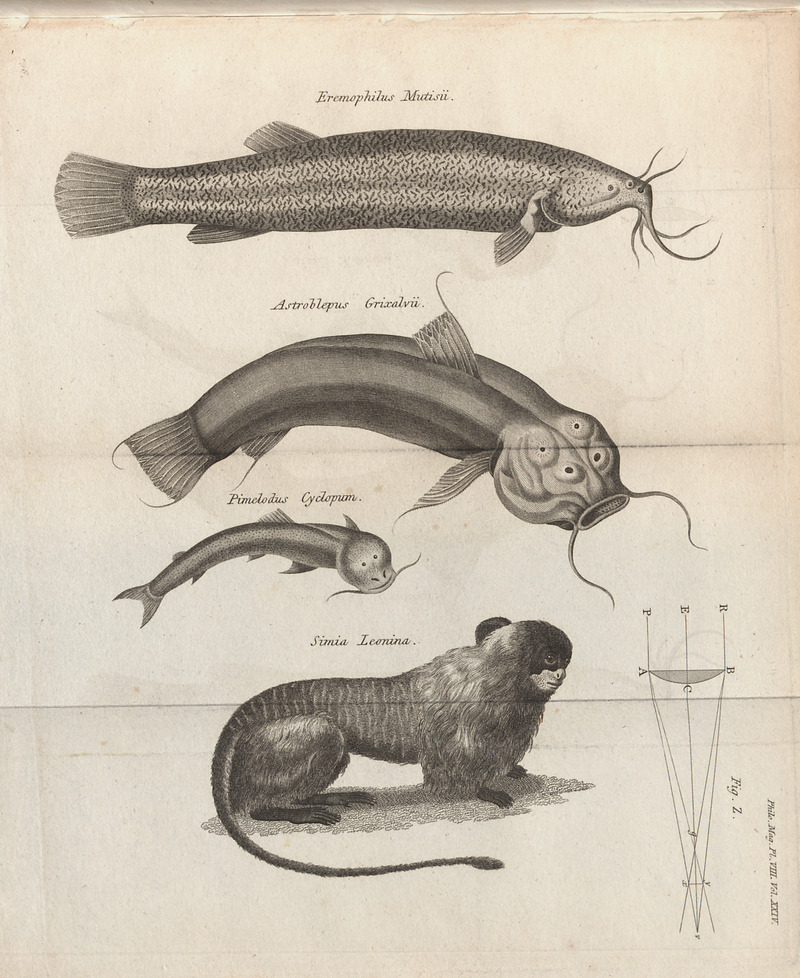

* M. Humboldt seems not to have been aware that this name has beenaffixed to it in consequence of its having some resemblance to a kind ofblackish coarse bread made of grits or pollard, and used in Spain by somevery poor but proud people, or for purposes of penitence in cases of a pecadomortal.—Translator. |335| canoes. On the estates of the marquis of Selvalegre theCotopaxi had thrown a quantity so great, that their putre-faction spread a fetid odour around. In 1691 the almostextinguished volcano of Imbaburu threw out thousands onthe fields in the environs of the city of Ibarra. The putridfevers which commenced at that period were attributed tothe miasma which exhaled from these fish, heaped on the sur-face of the earth and exposed to the rays of the sun. Thelast time that Imbaburu ejected fish was on the 19th of June1698, when the volcano of Cargneirazo sunk, and thousandsof these animals enveloped in argillaceous mud were thrownover the crumbling borders. The Cotopaxi and Tungurahua throw out fish, sometimesby the crater which is at the top of these mountains, sometimesby lateral vents, but constantly at 2500 or 2600 toises abovethe level of the sea: the adjacent plains being 1300 toiseshigh, one may conclude that these animals issue from apoint which is 1300 toises more elevated than the plains onwhich they are thrown. Some Indians have assured methat the fish vomited by the volcanoes were sometimes stillliving in descending along the flank of the mountain: butthis fact does not appear to me sufficiently proved: certain itis, that among the thousands of dead fish that in a few hoursare seen descending from Cotopaxi with great bodies of coldfresh water, there are very few that are so much disfiguredthat one can believe them to have been exposed to the actionof a strong heat. This fact becomes still more striking whenwe consider the soft flesh of these animals, and the thicksmoke which the volcano exhales during the eruption. It ap-peared to me of very great importance to descriptive naturalhistory to verify sufficiently the nature of these animals.All the inhabitants agree that they are identical with thosewhich are found in the rivulets at the foot of these volcanoes,and called prennadillas * : they are even the only speciesof fish that is discovered at the height of above 1400 toises

* This word is an indifferent or contemptuous diminutive, indicating abun-dant, pregnant, fruitful, easily taken, but not a pleasing or desirable object.The name is purely Spanish and not Indian, of course could never have beenapplied to any fish used as food by Spaniards.—Translator. |336| in the waters of the kingdom of Quito. I have designed it,with care, on the spot, and my design has been coloured byM. Turpin. I have observed that the prennadilla is a newspecies of the genus silurus. M. Lacepede, who has alsoexamined it, advised me to place it in that division of silurus which, in the fifth volume of his Natural History of Fishes,he has described under the name of pimelodes. This new species of pimelodus has a depressed body of anolive colour mixed with little black spots. The mouth, whichis at the extremity of the nose, is very large, and furnishedwith two barbillons or whiskers attached to the jaws. Thenostrils are tubulous; the eyes are very small, and placedtowards the middle of the head. The skin of the body andthe tail is covered with an abundant mucus, and the mouthis furnished with very small teeth. The branchial membranehas four radii, like the pimelodus chilensis; the pectoral finhas nine; the ventral five; the first dorsal six; the fin of theanus seven; and that of the tail, which is bifid, has twelveradii. The first radius of all the fins is indented on the out-side: the second dorsal fin is adipose, and placed near thetail. This little pimelodus, which is found in lakes even tothe height of 1700 toises, is, without doubt, the fish thatlives in the most elevated regions of our globe. Its commonlength scarcely amounts to ten centimetres (four inches);but there are varieties which do not appear to reach five cen-timetres (two inches) in length. In the system of ichthyology this new species of pimelodus should be ranged in the first sub-genus established by Lace-pede, among the forked-tailed pimelodes. It must be in thefirst species, before the pimelodus bagre. As it is the onlyone of that division that has but two whiskers, I give it thename of PIMELODUS Cyclopum. (Plate VIII.) Cirris duobus, corpore olivaceo nigro-punctato. This little fish lives in rivulets at the temperature of 10°of the centigrade thermometer, while other species of thesame genus exist in rivers in the plains the water of which isat 27°. The pimelodus is but very rarely eaten, and then |337| only by the most indigent race of Indians; its aspect andthe sliminess of its skin render it very disgusting. From the enormous quantity of pimelodes that the vol-canoes of the kingdom of Quito occasionally discharge, onecannot doubt that country contains great subterraneanlakes which conceal these fishes; for the individuals thatexist in the little rivers around are very few in number.A part of those rivers may communicate with the subterra-nean pits: it is also probable that the first pimelodes whichhave inhabited these pits have mounted there against thecurrent. I have seen fish in the caverns of Derbyshire, inEngland; and near Gailenreuth, in Germany, where thefossil heads of bears and lions are found, there are livingtrouts in the grottoes, which at present are very distant fromany rivulet, and greatly elevated above the level of the neigh-bouring waters. In the province of Quito, the subterraneousroarings that accompany the earthquakes; the masses ofrocks that we think we hear crumbling down below theearth we walk on; the immense quantity of water thatissues from the earth in the driest places during the volcanicexplosions; and numerous other phænomena, indicate thatall the soil of this elevated plain is undermined. But, if it iseasy to conceive that vast subterranean basins may be filledwith water which nourishes fishes, it is more difficult to ex-plain how these animals are attracted by volcanoes thatascend to the height of 1300 toises, and discharged eitherby their craters or by their lateral vents. Should we sup-pose that the pimelodes exist in subterranean basins of thesame height at which they are seen to issue? How conceivetheir origin in a position so extraordinary; in the flank of acone so often heated, and perhaps partly produced by vol-canic fire? Whatever may be the source from which theyissue, the perfect state in which they are found induces usto believe that those volcanoes, the most elevated and themost active in the world, experience, from time to time, con-vulsive movements, during which the disengagement of ca-loric appears less considerable than we should suppose it.Earthquakes do not always accompany those phænomena.Perhaps, in the different concamerations that may be ad- |338| mitted in the interior of a volcano, the air is found occa-sionally condensed, and that it is this condensed air whichcontributes to raise the water and fish; perhaps they issuefrom a concavity distant from those which emit volcanicfire; possibly, in fine, the argillaceous mud in which thoseanimals are enveloped defends them from the action of greatheat. Notwithstanding all the researches that have been re-cently made on volcanoes, there is nothing but the study ofvolcanic productions that has made any progress. As tothe nature of the combustibles which nourish those sub-terranean fires, and the mode of action of those fires them-selves, I believe that all persons who have visited the bor-ders of craters, and who have lived a long time in the vici-nity of volcanoes, will sincerely avow, with me, that we arestill very far from being able to give an explication, which,without being contrary to the principles of chemistry and ofphysics, could account for the great phænomena which vol-canic explosions present. The corregidor of the city of Ibarra, don José Pose Pardo,has communicated to me an interesting observation on the pimelodes. “It is known (says he, in a letter which I havestill preserved,) that the volcano of Imbaburu, at the timeof its great eruption on the side next our city, threw out anenormous quantity of prennadillas: it even continues stilloccasionally to do so, especially after great rains. It is ob-served that these fishes actually live in the interior of themountain, and that the Indians of S. Pabla fish * for themin a rivulet at the very place whence they issue from therock. This fishery does not succeed either in the day orin moonlight: a very dark night is therefore necessary, asthe prennadillas will not otherwise come out of the volcano,the interior of which is hollow.” It appears, then, that thelight is injurious to those subterranean fishes, which are not

* This is an assertion somewhat contrary to that of their being very badfood, and disagreeable in appearance. It is within the particular knowledgeof the translator, that the Spaniards of South America are both very scep-tical and very witty, and that to play upon the philosophical faith of Eu-ropeans would be their highest delight. He must therefore be pardoned forregarding the letter of el Senor Corregidor as a jeu d’esprit en revanche for thesarcastic observations of French travellers on the Spaniards.—Translator. |339| accustomed to so strong a stimulus: an observation so muchthe more curious, that the pimelodes of the same species,which inhabit the brooks in the vicinity of the city of Quito,live exposed to the brightness of the meridian sun.